English-language news in a non-English speaking country – why it makes sense

The adoption of English, even for domestic units in institutions or corporations, is a logical step. Especially for in-house newsrooms.

Many large corporations, research facilities and universities have English-language newsrooms or news hubs for both in-house and external news. A seven-year experiment at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, offers unique insight into the advantages and disadvantages of English-language versus native-language news. It can be applied to other large institutions and corporations throughout the world.

English is the global language of commerce and science, and more and more multinational companies and institutions are mandating English as their ‘corporate’ language. The adoption of English, even for domestic units in institutions or corporations, is the next logical step.

Let’s say a group of marketers in the Oslo headquarters of a Norwegian multinational is discussing a new advertising campaign. They may be more comfortable speaking in their native Norwegian, but this keeps their colleague in Brazil from contributing. And when the outcome is agreed upon, the terms that everyone tacitly agrees upon in Norwegian has to be subtly translated into English every time it is explained to a non-Norwegian speaker. The result: Confusion.

Universities and research facilities are also moving to English.

As more and more peer-reviewed science is carried out and reported in English, the writing of dissertations and recognized papers in a native language becomes harder and harder for the individual scientist.

Critics have pointed out, rightly, that this has irretrievable consequences for universities’ native languages. They slowly, but inevitably, lose the vocabulary of scientific advances. The non-English languages are, in other words, subject to ‘domain loss’, becoming purely languages of everyday life, and subject to no creative expansion of their own research vocabulary. But the fact is, for all languages except English, the domain loss has already irretrievably happened in the natural and social sciences and even human sciences.

Reporters at the University Post in Copenhagen

This was the context of a 2009 University of Copenhagen decision to allow me to set up a small in-house English-language newsroom, the ‘University Post’ (with one employee, me) in parallel to an already existing Danish-language one the ‘Uniavisen’ (with four hired employees, who also produce a bi-monthly newspaper).

The University of Copenhagen has a large group of international students, scientists and staff, and has a Danish/English parallel-language policy. The idea was that an English-language news service would not only cater to the non-Danish group, but would reinforce the the university’s international brand and internationalization policy.

For newsrooms, language is not just language

However, the dynamics of reporting in an international language ended up changing the whole outlook and strategy of the newsroom.

Let us start by looking at target audiences.

In the beginning, the small University Post newsroom attracted only traffic from non-Danish speaking international students and scientists at the University of Copenhagen. This meant that it started off by receiving relatively less traffic than the Danish-language news site Uniavisen which had more staff working stories and a (at first sight) larger Danish pool of scientists and students as potential readers.

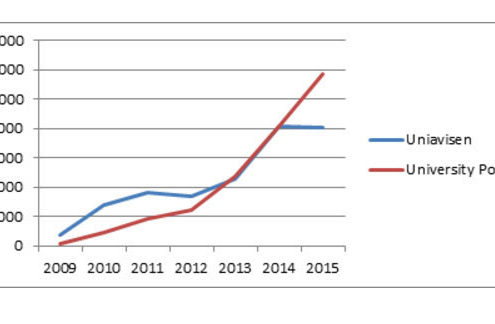

However, within a few years, the University Post surpassed the Danish-language site in traffic (see graph below), and this in spite of the fact that it was still running on one hired staff member (yours truly!) against their four. How and why did this happen?

Graph above: Website traffic on Uniavisen.dk and on UniversityPost.dk

I could at this point just brag and say that it was because I was a better editor than my Danish counterpart. But I suspect there are other, deeper, causes at play.

Tapping into the global niche audiences

When I looked at the web analytics data, I could see that certain types of stories were getting large amounts of traffic both at home and abroad.

They were specialist-interest stories that would not have a wide audience in a local language, but which would be interesting to a very particular, and very disparate group,throughout the world.

We ran a story about a University of Copenhagen scientist building a lego-model of a part of the Large Hadron Collider accelerator. It suddenly picked up, went viral within the physics-interested community and picked up 30,000 pageviews within just a few days. Another story about a scientist’s insect as food project garnered 90,000 clicks in a week.

Other stories were maybe not so popular, but touched on an intense scientific debate within a particular field. The debate would only be interesting to a few readers in Denmark, but when these readers are multiplied to the global audience the numbers become substantial.

Knowing that this effect was taking place, the University Post could then systematically orient its journalism towards these niche audiences, making further gains in traffic, and ultimately in value to the reader, the contributing authors, and the University of Copenhagen.

When you debate, you want everyone in on it

The second factor behind the English-language University Post’s dominance is the debate and the readers’ reactions and input. This means the comments under the articles and the featured comments offered to us by our readers for publication in the opinion section.

If you have the choice between two languages, most people prefer to comment in the language that is inclusive of the highest number of their potential readers. Notice how many non-English natives comment in English on Facebook? It is the same effect. Although there may be a minority of readers who have problems understanding English in a given community, so long as this minority is not substantial many commenters will as a default prefer to comment in English. It is simply more inclusive, and given the above-mentioned domain loss, is easier when discussing subjects of a technical nature.

With this effect in mind, articles on the University Post, even those which were covering exactly the same news events as the Danish-language Uniavisen, in Copenhagen, would attract much of the debate on the subject, even from the Danish readers.

The power of the CV

A final factor behind the relative success of the English-language University Post is the prestige-seeking behaviour of the contributing students and scientists.

Some of the content on the University Post is contributed by students and scientists for free, while other content (assigned news stories) is paid for in the form of our student reporters receiving a small fee. For both groups of contributors there is a larger incentive to contribute, when your story, photo or set of data, will be published on a site in English.

Links to articles are typically uploaded onto reporters’ LinkedIn profiles for future global employers to see. Employers already take for granted that every student and scientist can read and write in their own native language. But by publishing on an English-language media, students and scientists can prove to employers that they also read and write in the language of global business, science and policy.

The result? We get hundreds of applications from students and volunteer contributors of high quality, all wanting to contribute to the English-language site. The Danish-language Uniavisen site on the other hand, has a much harder time attracting contributors.

The translation trap

So what did we learn?

The first thing is that having the same stories in two languages with translations back and forth from non-English-language news stories to English-language news stories is almost never the answer.

There is the time-lag problem:

Let us look at the first option. If you publish on the non-English news site first, then translate, then publish on the English-language news site. Here, the English-language readers have to wait for the story. This effectively shuts them out of the debate, which normally takes place within seconds or minutes at the moment of publishing – cued by the first person to comment.

Then there is the second option, the other way around. An English-language story published first, translated, then published in the native-language. This will work the other way around, shutting out a native language story from the debate..

Then there is a third option. Translate first, then publish in both languages simultaneously. Sounds fair, right? Maybe fair to both language groups, but you are also effectively penalizing all readers by forcing them to wait for the translation process to finish. This also exacerbates a specific debate problem. Commenters under one article, will be starting a second, different comment thread than the same article in another language.

But there is a more fundamental problem to translating and having the same content on two platforms.

It presupposes that the news event and report is of interest to the same type of reader who has the same interest but just happens to prefer a different language. This, as our discussion of the global niche audiences is an example of, is often not the case. Readers are different, and many native readers (say Danish) with global niche interests are much better served with an English-language article that she can debate with and contribute to in an international language, than one in her native tongue.

Recommendations for other institutions, organisations and companies

English-language newsrooms in non-English speaking countries are quite common. I asked a few days ago for the names of news sites that do this on the LinkedIn group Online reporters and editors. I so far have 32 responses.

In Copenhagen, at the University Post, we have experience and data on the use of English-language media in a native-language context. Initially the experiment was considered simply a service to international staff and students. But the logic and dynamic of the internationally dominant language proved that in the long run, native and non-natives preferred to click, read and interact in English.

This has policy implications for other large institutions and corporations with global aspirations who have embedded newsrooms for staff, customers and stakeholders.

Based on our experience, I recommend the following:

1) Just do it. Don’t slowly roll-out a move into English, but go all the way, fast, with confidence. Staff, students at the University of Copenhagen were willing to read and contribute in a language that in most cases, was not their own. Make the break and go for it 100 per cent.

2) Don’t make a parallel structure in one newsroom with two languages. It doubles staff and ressources, takes up work in terms of translation, and divides the debate and comment threads between two language groups. If you have to work in two languages, split the newsroom.

3) Work with your global niche. Make your newsroom the place where experts from different countries debate specific issues.

4) Make it good for your contributors! They thrive on the (global) readers’ interest in their expertise, the skills and practice that they get, and the career boost that English-language writing offers them.

I am looking forward to any comments you may have on this! Feel free to either comment here, message me or e-mail to mike@mikeyoungacademy.dk.

Interessting stuff 😉