The TwiLi Index – a new method to count scientists’ social media following

Simply adding up followers doesn’t make sense. This new method is better, I reckon, and can be used as a proxy to assess scientists’ relative social media impact.

[This post was updated in September 2022]

I wanted to do this for an awful long time: Find a method that could compare follower numbers on the social media platforms that are the most used by scientists and researchers, namely Twitter and LinkedIn.

Living and working with science communication in the Copenhagen area, I wanted also to use the Danish metropolis as a first test case to find out which researchers and scientists would get on, say, a top 100 ranking.

What I cooked up, I hereby (drum roll!) name the ‘TwiLi Index’ (pronounced like ‘Twilight’ without the ‘t’) . Its first application was seen in 2019, where I ranked the top 50 scientists and researchers in the Greater Copenhagen / Øresund region.

The latest (2022) rank of scientists in Denmark can be found here.

Previous TwiLi Index ranking releases:

- Top 100 scientists in Sweden 2022

- Top 100 scientists in Norway 2022

- Top 100 scientists in Denmark 2021

- Top 100 scientists in Denmark 2020

- Top 100 scientists in the Greater Copenhagen region in 2020

- Top 50 scientists in the Greater Copenhagen region in 2019

The problem

For good or for worse, scientists and researchers are assessed and evaluated by their ‘impact’. Most often, it is the number of scholarly citations that is considered the most important measure of this. Google Scholar, f.ex., shows researchers and scientists h-index, which is based on the scientist’s most cited papers and the number of citations in other scholarly work.

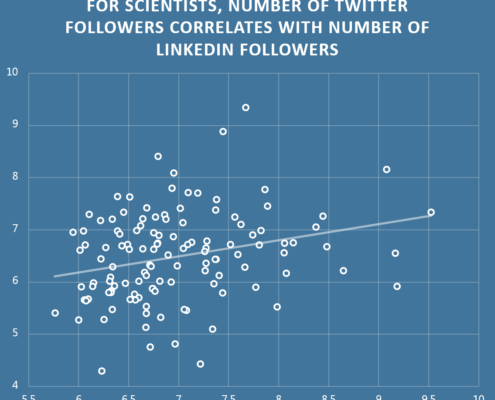

Each scientist is represented by a dot. On the x-axis is the log of their number of Twitter followers. On the y-axis is the log of their number of LinkedIn followers

At the same time, many scientists have embraced the use of social media to disseminate their research, and to network with other scientists. They are often supported in this by their affiliated university institutions that can improve their brand among stakeholders, other scientists, and the wider public if their own scientists are active on social media.

In all spheres of life nowadays, the number of social media followers correlates with real, or certainly perceived, status. Academia is no exception, and follower numbers seem to correlate well with other measures of success.

The TwiLi Index is, I feel, a better, more honest, way to calculate the numbers.

The number of social media followers is visible, and important. If for nothing else then certainly as a ‘vanity metric’ that supports researchers and their institutions’ egos.

A well-known metric that calculates social media impact for researchers is the so-called Kardashian Index (K-Index), named after the pop star Kim Kardashian. It is a measure of the discrepancy between a scientist’s social media profile and their publication record. The measure compares the number of followers a researcher has on Twitter to the number of citations they have for their peer-reviewed work.

The trouble with the Kardasian index, which was invented by Neil Hall, is that the index itself is a criticism of scientists having to have a social media impact at all.

To slightly misquote the Good Book, ‘for every one who has followers, more will be given…’

The TwiLi Index is, I feel, a better, more honest, way to calculate the numbers. A high social media following for a scientist is, everything being equal, surely a good thing. But apart from that, I take no stand on the deeper issue of whether activity on social media, or (heaven forbid!) competition over social media impact is a good thing for science in general.

The method

You could just count followers.

But the trouble with just counting followers is that social media platform followings are susceptible to a runaway, Matthew, effect. To slightly misquote the Good Book, ‘for every one who has followers, more will be given…’ People are more likely to follow the accounts that already have many followers. And this effect is exacerbated by the effect of accumulation over time, so that the longer an account holder is active on an account, the higher the likelihood that he or she has many followers. This favours long-serving, distinguished researchers who have been at it a long time, and who are more likely to have a successful academic career behind them: Succesful professors who have many followers, tend to have many, many followers.

So if we are to compare social media following in any meaningful way, we need to reduce this effect. So my first intervention is to use a base 10 logarithm of the follower number to counteract it.

So if we are to compare social media following in any meaningful way, we need to reduce this effect. So my first intervention is to use a base 10 logarithm of the follower number to counteract it.

At the same time, the number of followers on one platform, say Twitter, correlates quite well with the number of platforms on another platform, say LinkedIn (see graph above).

As far as I can see, there are three reasons for this.

First and most important. If you have many followers on one platform, you likely already have the status and leverage that attracts followers on another.

Second, if you are very active/successful on Twitter, you are also likely quite active/successful on LinkedIn and vice versa, as you are predisposed to social media activity.

I think it works pretty well. Runaway numbers on one platform don’t give you an unfair advantage. And your index is higher if you have good numbers on both platforms, rather than low numbers on one and excellent numbers on the other.

Third, the posts and information that is accessed on one platform can be leveraged with success on the other, making your other platform more popular.

From this I deduce that just adding the base 10 log of Twitter followers to the base 10 log of LinkedIn followers does not capture this affect. That is why I propose multiplying the two numbers.

Finally I add 2 to each follower number. This is so that if you have zero followers, or only one follower, on one of the platforms, you can still get a meaningful TwiLi number.

The resulting formula is the following.

TwiLi Index number = log (2 + A) x log (2 + B)

Where A = number of Twitter followers and B = number of LinkedIn followers.

I think it works pretty well: Runaway numbers on one platform don’t give you an unfair advantage. Your index is higher if you have good numbers on both platforms, rather than low numbers on one and excellent numbers on the other. And the TwiLi Index ranks researchers in a different way than simply adding or even multiplying follower numbers.

Gathering the data

So how did I proceed in this, my first, tentative, case?

First off, and the most difficult part of it, is to try and find all the scientists in Denmark that have large follower numbers.

Luckily my own @MkeYoungAcademy Twitter account, which I have been running for several years and which tweets about seminars and lectures in the Nordic region, consistently follows and is followed by scientists and researchers in that region. So I used the group I was following as a starting set of data that I could augment as I went along.

I got some help at this point from my good friend and data scientist Lasse Hjort Madsen who helped me to extract good data from my Twitter account to a workable spreadsheet.

Since then, whenever I stumbled across a Twitter account that identified itself as a scientist in the region, I simply added them to the spreadsheet.

I ended up with a macro list with a set of upwards of 3,000 researchers. My daughter Atlanta Young, a historian by training and yet another data ‘ninja’ helped me at this point. She spent some time working up a reasonably fast routine to cross-check the researchers’ LinkedIn follower numbers.

Note here that we looked for LinkedIn followers, and not connections. Connections are, by default, followers. But not every follower is a connection. For most people the two numbers are nearly the same. However for top scientists, the follower numbers can be higher. The follower metric is more comparable to Twitter.

I am also hoping that scientists and researchers who are interested in this ranking – and this goes both for those who make up the top, and those who didn’t make it this time round – will give me feedback on my methodology.

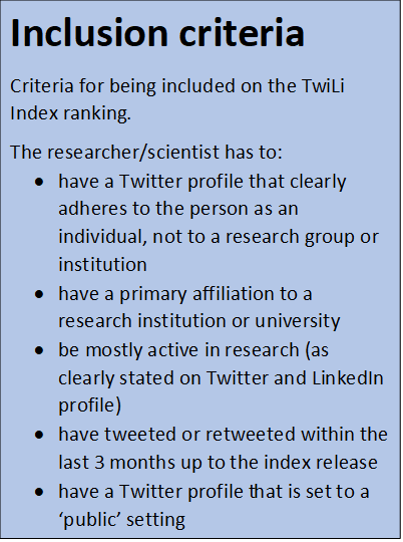

Some scientists were excluded from the list at this point, if they failed to live up to our inclusion criteria (see box above).

Now it was time to apply the formula to the data, and to extract the index. Here I was helped by Andreas Junge. He is a maths whiz who is the CEO of Methodica Ventures when he is not helping his friends with their pet data projects.

The result: The new Twi Li Index, which had its first iteration as a top 50 scientists and researchers in the Greater Copenhagen / Øresund region.

Other metrics of engagement and influence

The social media impact of a scientist cannot, of course, be measured by just putting follower numbers through a formula. There are other, more subtle, measures of social media influence, and my ambition was to find ones that would function in scientist networks.

I have had many a discussion with data scientist Lasse Hjorth Madsen about this, and we came up with two workable measures that we applied in 2021, namely ‘centrality’ and ‘pagerank’. For this, Lasse developed a bespoke web app for Mike Young Academy to organise a set of publicly available data that was extracted using the Twitter API.

My dataset now consists of more than 3,000 scientists and researchers, but new scientists are being added all the time.

I decided not to integrate Twitter centrality and Twitter pagerank directly into the scientists’ TwiLi score, but list it separately for each of the scientists that made the top 100. I want to keep the TwiLi score separate so scientists can compare their own score with previous years. Also, the beauty of TwiLi is that everyone can check out their own score, just by plotting in their own numbers. This is not the case with centrality and pagerank, which is a far more data-intensive calculation.

Centrality

Centrality — or technically ‘betweenness centrality’ — sees scientists as hubs for flows of information on Twitter. A scientist has centrality on Twitter if they are shortest pathway between two other people on the Twitter network of scientists. Say Jill follows me, and I follow Jack. If Jill and Jack don’t follow each other directly, then I am the shortest pathway between them. You score high on centrality if you are the shortest path between others many times. Centrality in this case has been calculated based on a network of more than 3,000 scientists on Twitter in Denmark. So if you are a scientist with a network that is mostly abroad, you may score lower on centrality in Denmark.

Pagerank

Pagerank, a measure inspired by Google’s original namesake algorithm to rank websites on google searches, sees scientists as attractors of influential followers. It is an indirect, proxy measure of scientists’ impact based on their followers’ follower numbers on Twitter. A scientist has a high Twitter-pagerank if if the people who follow them have many followers. So getting followed by another scientist who has a high following on Twitter improves your own pagerank. However, getting followed by media and journalist Twitter accounts with many followers will also increase your pagerank. This means that pagerank may favour scientists well-known for other things like politics, business, sport or in fields that are in the public eye.

What now?

My dataset now consists of more than 4,500 scientists and researchers, but new scientists are being added all the time.

My hope is that each summer, I will be able to redo the ranking based on the same methodology. Hopefully with more comprehensive and accurate datasets, and in new geographical areas.

I am also hoping that scientists and researchers who are interested in this ranking – and this goes both for those who make up the top, and those who didn’t make it this time round – will give me feedback on my methodology.

I appreciate any help! Feel free to leave any feedback in the comments below. Or write to me on mike@mikeyoungacademy.dk if you know someone who needs to be on a ranking who I have missed.

My sincere thanks and appreciation go to Lasse Hjorth Madsen, Atlanta Young and Andreas Junge for feedback and help with this project!

Does your department, faculty or university need to boost the international impact and career of your researchers? Here is more about my courses in social media for researchers. See other Mike Young Academy services here.

That’s great stuff Mike. Wicked formula;) Can’t wait to see this index applied to a larger community. Other cities maybe?

Thanks Andreas! Soon coming to a city near you 🙂

If #twitter followers correlates with #LinkedIn followers as claimed just use twitter. Why? Because sane folk like me gave up LinkedIn when it started spamming me. It provides ZERO benefits to me. I have an H-index of 107 on GS and 86 I think at WoK. How do your top 50 fare?

Thanks for your comment Douglas. I don’t agree. I think LinkedIn offers benefits. Both on its own, and in conjunction with Twitter. The search functionality is very powerful, and has many research networking applications. And the platform is ideal for forging relationships with people outside your own niche field, and outside academia. As for how my top 50 fares on H-index: I looked into it, but haven’t compared my top 50 systematically with another sample of researchers. I would leave the Kardashian formula for that! Also: The trouble with H-index for the sample is that it is so biased against the human and social sciences. So I deliberately delimited this ranking to social media following. best Mike

Interesting index. Nice one! Question…does “social media platforms that are the most used by scientists and researchers, namely Twitter and LinkedIn” still hold true in 2022 (and what is that original quote based on)? I’d suspect that instagram and tiktok might being giving both a run for their money, particularly if you split the data set by age i.e. younger scientists are using those platforms a lot and many do not use linkin and twitter at all.

Thanks for your comment Lachlan! Regarding your question: I think it still holds true. At least if you define ‘most used’ as social media platforms that scientists use professionally for networking with their peers. I haven’t seen recent numbers on it, but before my social media workshops I always survey the participating scientists. Twitter and LinkedIn are always at the top. That said: I would love to do some work with numbers on Instagram and Tiktok. Let me know if you have any ideas for helping me with this 😉

You seem to have developed a metric that measures the potential for individuals to influence others via social media due to the size of their networks. That’s all fine, but I object a bit to your use of the word “impact” here. This is a term that has quite a specific, but very often misunderstood, definition in research evaluation contexts and your metric does not fit the bill at all. Being active on social media, and having a large network is all well and good, but at most you are measuring communication/dissemination activity and potential to generate impact, but not impact itself. It’s a bit like the difference between publications and citations. Lots of publications means that you are productive – lots of citations means that people are actually reading your work and using it (impact).

Thanks Craig for your insightful comment. I am not an expert on research evaluation, but I agree with all of your points. My use of the word impact in describing the index does not fulfill the stricter definition of impact. My index is in this sense not a proxy for impact as I state (and maybe not even a proxy for a proxy!). Impact is simply in the everyday use of the term. In a more self-critical vein: I sometimes think that my index just measures something like ‘status of scientists’ or something like that, and not even ‘potential for dissemination impact’. What keeps me going with doing these indices though is the belief, that some insights are to be had from ranking scientists in this way as a supplement to all the other ranking going on. For example, it is interesting to see relatively unknown scientists or early stage scientists score higher. Or how research-age and research field affect things. For me it is a work in progress! best Mike

Thanks for your reply. I agree that network centrality and size are a good proxy for the social media influence of a scientist. I’m just concerned about the use of the word “impact” and the potential for it to create more confusion around the concept of research impact – an already very confused topic thanks to metrics like the Journal Impact Factor!

Yes I see where you are coming from Craig. Now I will be more aware of how I use this term.