How to be kind on social media – a guide for scientists

11 ways to make your social media presence reflect the best of what science can be

Let’s make kindness the new norm on social media!

Extract from ‘The School of Athens’ (1509-11) by Raphael

By consciously cultivating a culture of kindness in our online interactions, we actively maintain a social media space around us where ideas are shared, critiques are constructive, and connections are genuine in the scientific community.

It is not just about being polite – it’s about setting off a positive chain reaction, and ultimately helping the advancement of science.

By treating other scientists on social media with kindness, we can better foster innovation, ideation, and intellectual growth in the academic community.

I recently committed Mike Young Academy to the Excellence and Kindness in Research Initiative (ELIS), and this inspired me to set up examples of kind scientist interactions. Have I forgotten any ways to be kind on social media as a scientist? Let me know in the comments, and I will iterate this list as we go along!

Be a force for the good!

The 11 kind habits

1. Post with gratitude

Sharing your findings is not just about boosting your h-index. It’s about contributing to the scientific community. Your research builds on the work of countless others, and in turn, your findings might serve as the foundation for future discoveries. When you share your work, you are paying forward the generosity of those who came before you.

Example: Publicly thank a mentor or collaborator for their support on a project on LinkedIn: ‘Couldn’t have completed this without the guidance of @MentorName — your insights were invaluable!’

Example: Publicly thank a mentor or collaborator for their support on a project on LinkedIn: ‘Couldn’t have completed this without the guidance of @MentorName — your insights were invaluable!’

Also: Always remember to acknowledge by tagging with ‘@’ the producers of texts, graphics and photos that you share.

2. Offer as many details — as you can

Share as much of your doubts about data and methods as you can on social media. You might worry that this openness could expose you to criticism or that someone might ‘scoop’ your work. And sometimes there may be other reasons to not share data or methods before publication. We all need space for reflection and feedback from a smaller group before we are willing to share our research. But often the caveats and fears are unfounded. When you share your ongoing concerns, you invite collaboration, encourage replication, and help others to build on your work.

Example: In your social media update, link to a blog post where you openly summarize and discuss any challenges or uncertainties you faced during your research. For example, ‘During our study on Y, we encountered some unexpected results that we’re still trying to understand. We initially hypothesized A, but our data suggested something different. If anyone has insights or has faced similar issues, I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Example: In your social media update, link to a blog post where you openly summarize and discuss any challenges or uncertainties you faced during your research. For example, ‘During our study on Y, we encountered some unexpected results that we’re still trying to understand. We initially hypothesized A, but our data suggested something different. If anyone has insights or has faced similar issues, I’d love to hear your thoughts.

3. Amplify others’ work

Social media platforms can elevate the impact of others, particularly those who may not have the same reach or recognition as yourself. It might seem counterintuitive to promote others when you are striving for your own recognition within a given field. But when you retweet a colleague’s paper, even a colleague who is doing ‘competing’ work close to your own field, you are contributing to a more inclusive and supportive scientific community.

Example: Repost a colleague’s publication announcement on X with a comment like, ‘Don’t miss this important paper on B by @ColleagueName — great contribution to our understanding of C!’

Example: Repost a colleague’s publication announcement on X with a comment like, ‘Don’t miss this important paper on B by @ColleagueName — great contribution to our understanding of C!’

4. Share your failures

Share the challenges, the failed experiments, the rejections. This doesn’t mean wallowing in negativity, but rather providing a balanced view of what it means to be a scientist. Your authenticity can help demystify the process for others, particularly for early-career scientists who might feel isolated in their struggles.

The University of Graz in Austria even goes as far as to encourage an error-friendly research culture with its Forum of Failures and Fiascos Repository.

Example: Post about a failed experiment or rejected grant on LinkedIn, sharing what you learned from the experience. For example, ‘While this grant didn’t go through, the feedback was invaluable and has strengthened my future proposals. Happy to discuss if anyone’s interested in what I learned.’

Example: Post about a failed experiment or rejected grant on LinkedIn, sharing what you learned from the experience. For example, ‘While this grant didn’t go through, the feedback was invaluable and has strengthened my future proposals. Happy to discuss if anyone’s interested in what I learned.’

You can even share it without saying what you learned from the experience. In many ways, this can be better, as it does not presume that your failure is actually a ‘success’.

‘I just received word that my grant application for [project] wasn’t successful. I will get over it, but right now it’s a tough pill to swallow.’

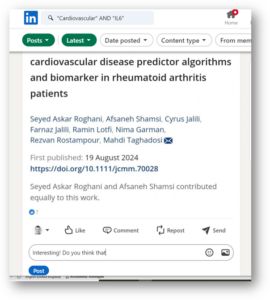

5. Give constructive feedback

When a colleague shares a link to their research, your first inclination is to ‘like’ it, because you want to show your appreciation and help your colleague’s post do well with the algorithms. This is fine. But this is also the point to provide  specific, constructive comments that promote further reflection — also among others who see your colleague’s post.

specific, constructive comments that promote further reflection — also among others who see your colleague’s post.

Example: Reply below an X post (tweet): ‘This is a fascinating approach to A. Have you considered how B might influence your results? I’d love to discuss this further.’

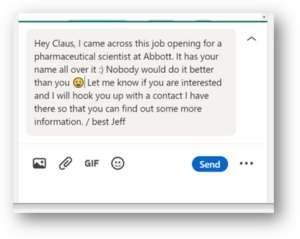

6: Connect other people (for their sake, not yours!)

In a field as competitive as academia, it can feel hard to have the energy to promote others when you are also striving for your own recognition.

But it’s not just about you. When you retweet a colleague’s paper, highlight an early-career researcher’s achievement, or share a thoughtful thread from a lesser-known scientist, you are contributing to a more inclusive and supportive scientific community.

Your goal should be to enable new thought, not to ‘win’ an argument.

By introducing your connections to others who might benefit from knowing each other. It should create value for both parties. Maybe there is a job offer, a research collaboration opportunity, or a course that you think another person should be aware of. Maybe they just share a common interest.

Example: Write a direct LinkedIn message to A: ‘Hey A, I came across this job opening for a pharmaceutical scientist at [Company Name]. It seems like a great fit, especially with your experience with [specific skill or project]. You’d be a strong candidate.”

Example: Write a direct LinkedIn message to A: ‘Hey A, I came across this job opening for a pharmaceutical scientist at [Company Name]. It seems like a great fit, especially with your experience with [specific skill or project]. You’d be a strong candidate.”

Alternatively, introduce two people in your network who might benefit from knowing each other: “@Person1, meet @Person2—both of you are doing fantastic work on F and might find some great synergies!’

7. Respond thoughtfully

It can be tempting to react immediately to a post, particularly if it challenges your views or position, or if you perceive it as an encroachment upon your own status in a field.

But you should take a moment to think before you respond. Is your comment adding value to the conversation? Are you respecting the original poster’s perspective, even if you disagree? A rushed or poorly considered reply can discourage someone from sharing their ideas in the future.

But you should take a moment to think before you respond. Is your comment adding value to the conversation? Are you respecting the original poster’s perspective, even if you disagree? A rushed or poorly considered reply can discourage someone from sharing their ideas in the future.

Resist the urge to dominate the conversation. Your goal should be to enable new thought, not to ‘win’ an argument. This approach is not only kinder but contributes to a healthier, more productive, and more intellectually stimulating scientific discourse.

This ties in well with the thoughts expressed by Venkatesh Rao, an Indian-American author and consultant who referred to social media, as the ‘global computer in the cloud’. There is something noble, something human, and something productive on it. But to participate in it, you have to be willing to stop using it strategically to communicate a message that has already been prepared.

Respect your audience’s intelligence and engage in real dialogue, even if you suspect (inside!) that your audience will find it difficult to grasp

Social media platforms amplify those with the ‘loudest’ voices so they dominate newsfeeds. Make a conscious effort to listen to those softer voices who are either not represented at all, or who are drowned out by all the heavy hitters. This isn’t just a nice thing to do — it’s an ethical responsibility.

Example: Set up a bookmarked LinkedIn search with keywords related to your field, such as ‘neuroscience research’ or ‘supercritical fluids’, and filter for your location, or for your university. This search will act as an alternative newsfeed, bringing up posts and discussions from your own institution from early career scientists that are not in your own network and that have not been fed to you by the LinkedIn algorithm. Regularly thoughtfully comment on the posts that are valuable, but that have not set off long discussions.

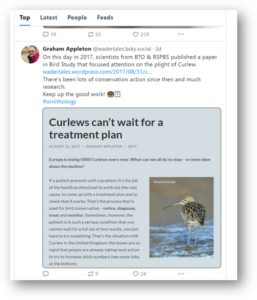

8. Promote reflection and slowness

8. Promote reflection and slowness

The urgency of the new on social media creates a sense of vertigo and stress on the platforms used by scientists: If you don’t follow your field on a day-by-day basis you are somehow ‘behind’.

Fight this focus on the new. By having a routine to repost older, yet still relevant, content from your network you can push back against the underlying premise of social media in science: That it is only the place for the ‘latest’.

Deliberately repost posts from your network that are NOT the latest showing up on your feed. This could be something that is still relevant, but that was posted a year ago.

Example: Set up a throwback science routine, perhaps weekly or monthly, where you resurface valuable older posts from others. Give it a name like ‘Throwback Science’ or ‘Timeless Insights’. Credit the original poster, and express appreciation for their contribution in the post. You can ask open-ended questions like, ‘How have your views on Z evolved since this was originally posted?’

9. Assume good intent

By assuming that others are engaging in good faith, scientists can foster a more constructive and respectful dialogue. This is particularly relevant in science because discussions often involve complex, nuanced topics where misunderstandings can easily arise.

Example: Someone posted about your paper on Bluesky: ‘Interesting paper on climate modeling, but I think the authors overlooked some key variables in their analysis.’

Here is an example of a response under this post that is not assuming good intent: ‘Clearly, you didn’t read the methodology section properly. The variables you’re talking about were accounted for.’

Here is an example of a response under this post that is not assuming good intent: ‘Clearly, you didn’t read the methodology section properly. The variables you’re talking about were accounted for.’

Never, ever, using the word ‘groundbreaking’ in any post that is not about digging holes in the ground!

And here is an example of a response assuming good intent: ‘Thanks for pointing that out! It’s a complex area — could you elaborate on which variables you think were missed? I’d love to understand your perspective.’

10. Trust that other people are bright people

10. Trust that other people are bright people

Respect your audience’s intelligence and engage in real dialogue, even if you suspect (inside!) that your audience will find it difficult to grasp:

Example: When responding to questions or comments, approach them as an opportunity for dialogue rather than a one-way teaching moment. Instead of correcting someone bluntly, say, ‘That’s an interesting point. Have you considered how Y might influence Z?’ This opens up a conversation rather than shutting it down.

11. Be sincere

Literally ‘groundbreaking’ (and AI-generated by Dall E)

This means no clickbait. No sexing up. And it means never, ever, using the word ‘groundbreaking’ in any post that is not about digging holes in the ground!

Example: Write a thread on X with all the caveats: ‘This new paper on E has some interesting findings, but keep in mind the small sample size. Worth discussing!’

So that’s it! Have I forgotten any practical ways in which you can be kind on social media as a scientist? Feel free to write them in the comments.

Does your department, faculty or university need to boost the international impact and career of your researchers? Here is more about my courses in social media for researchers. See other Mike Young Academy services here.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!